Game Media Industries: The beginning of the fun bit!

Week 3: Pitch

As detailed in my Pitch, for my DA I’m working on Concept Art this semester, using the MDA Framework. I can’t wait to share more about the project!!

Week 7: Progress Report

Subnautica is a game about a lot of things: Crafting tools and building a base, uncovering secrets on an alien planet, and saving both your own life and the lives of the other inhabitants of the planet 4546B. The game is easy to get deeply invested in, and engagement can range from fluid to extreme (Leorke, D. 2022), depending on the player. Within my DA, I want to look at how the game engages players by looking at the production process- its concept art and the methods of design Unknown Worlds used to create the mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics within Subnautica.

But what exactly is MDA?

The Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics framework (MDA for short) is a framework of analysis intrinsic to our understanding of games and how audiences interact with game media (Hunicke, Zubek, 2004). It breaks down games into three distinct parts:

- Mechanics, the function of the game itself- what players can or cannot do within a game.

- Dynamics, the feedback systems in place that keep players engaged with the world and story, and how changes in both interact with player choices and actions.

- and Aesthetics, the player experience, their motivation, and how the game may be categorized (ie. Genre). (Hunicke, Zubek, 2004)

To take Subnautica for example, you need to find resources in the game to craft anything, a core mechanic of the game. The environment is full of rocky outcroppings you can destroy to find metals, plants to harvest for food and crafting supplies, and fish to hunt and kill. That player interaction with their environment produces a response, starting a dynamic feedback loop that teaches a player they need to go to these particular plants, biomes, and creatures for specific materials. The aesthetic design of said plants, biomes, and creatures then tells the player what they’re looking for, rather than 1,000 identical garryfish (actual fish name) and sandstone outcroppings that would significantly limit the player experience.

We can apply these ideas to pretty much every part of game design, as long as it has a connection to function, feedback, and response. This, then, places it as the perfect framework to analyse the role of Concept Art in video game production.

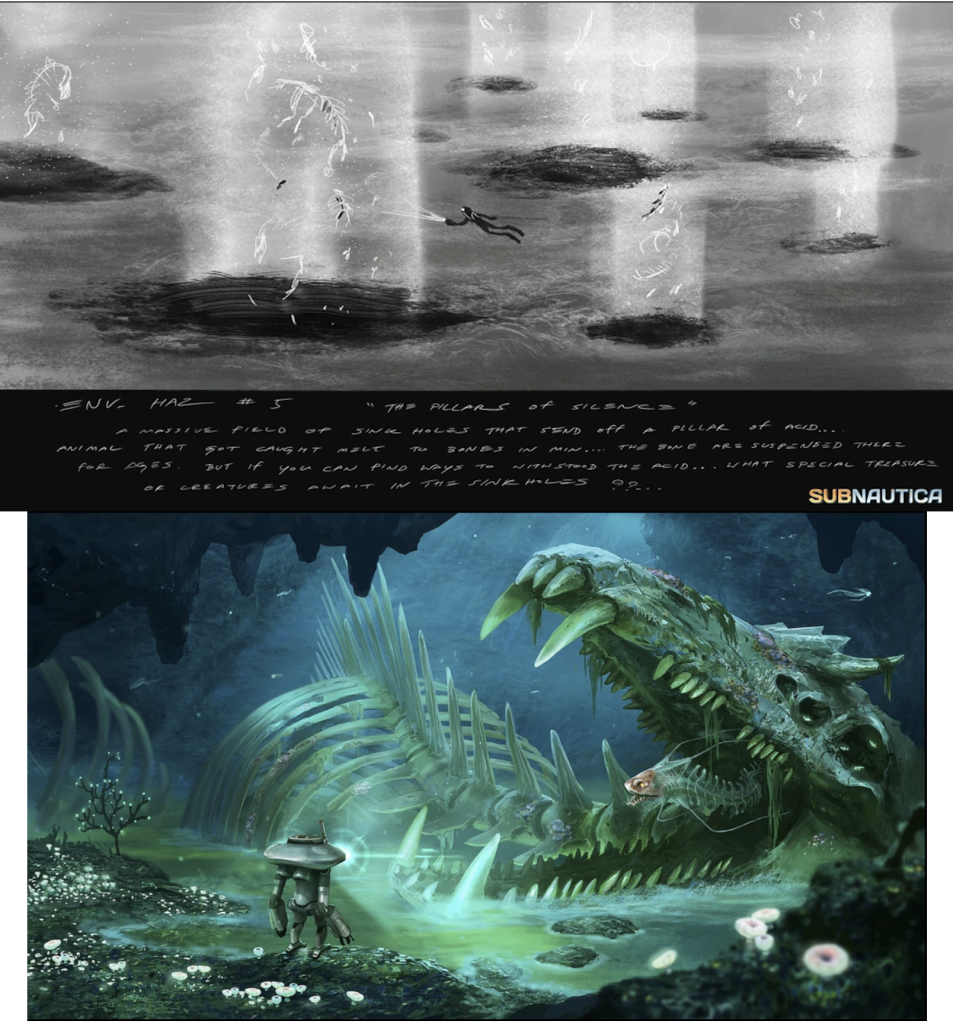

Analysis example: Early Art “The Pillars of Silence”

This piece of concept art (above) seems to be one from quite early in the process, as its black and white style points to it being a more developed thumbnail sketch- a simple drawing at the start of the design process used for the rapid prototyping of ideas. (Honkanen, 2017)

Looking at the image and written context below it, we can see the intended MDA of the environment. “The Pillars of Silence” were intended to be a biome important to finding resources, with the added layer of danger with the acid you would have to get through to reach anything useful. The art is eerie, and seems to imply a similar colour palette or environment to that of the lost river- a late-game area also featuring acid and needing to overcome it to find materials- with much more developed concept art pictured below.

Image cr.

Above: The Pillars of Silence, Anonymous, Unknown Worlds, n.d. Text reads: “Env. Haz #5 “The Pillars of Silence” – A massive field of sink holes that send off a pillar of acid… animal that got caught melt to bones in min… the bone are suspended there for ages. But if you can find ways to withstand the acid… what special treasure of creatures await in the sinkholes??..”

Below: Lost River concept art, Anonymous, Unknown Worlds, n.d.

When looking at concept art from an outsider’s perspective, we can only make educated guesses on a lot of the intended function of areas unless they made it into the final product. Concept art then, to an extent, becomes primarily focused on dynamics and in particular aesthetics, which makes sense given the visual and design-based nature of both art and the aesthetics part of the framework.

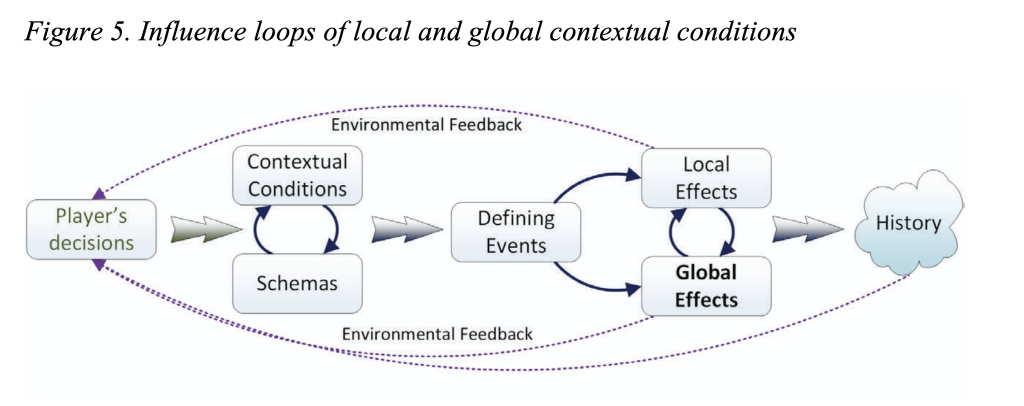

This flow chart outlines the feedback loop that can be applied to many games, such as Subnautica. Player actions based on the context they are in within the game world causes effects both immediately for the player and the world of the game, starting a chain of cause and effect as these effects change the player context and therefore their decisions (Fabricatore 2018). While not in effect in concept art due to the medium being strictly visual, a lot of development of ideas as to what these effects are happens within this stage.

Concept art is an intrinsic part of the game development cycle as it fills a major role in several parts of the process. It’s important for rapid prototyping with thumbnail sketches and continues to have an impact on game design as it influences not only mechanics and dynamics, but is also affected by them- the art style and some technical elements in particular are impacted, as mechanics impose restrictions on what can or can’t be done within the aesthetic sides of the game (Höök, 2023).

Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics influence each other just as much as they influence other elements of a game, and concept art is a significant part of all of them. Without visual development, most games would be a lot more boring and challenging and most people wouldn’t bother playing them. With how vital games are becoming to all kinds of contemporary media, the role of concept art and MDA will only continue to grow in relevancy.

So What About the Digital Artefact?

My digital artefact (DA) has changed somewhat since the Pitch, as they tend to do. This time, however, there’s a couple of distinct features of it that have changed, instead of the entire project:

- The subject of my concept art:

- Initially, I was working on art for my friend’s D&D-esque tabletop game, and while I still intend to do this in my free time, I found it was difficult to work within the restrictions of the assessment itself. Being unable to get feedback from people outside BCM215 due to ethics concerns, I would be unable to communicate with the friend running the game as I would in an industry context.

- The goal of my DA:

- This sounds like a major element, but really all that’s changed is that instead of looking specifically at atmosphere, I’ve shifted my goal to moreso look at how the production of concept art functions within the design process and game development cycle. This turns the more qualitative assessment of the previous idea into a quantitative one, being objective about the time it takes to produce, as well as the actual purpose of production art, as a game can’t be built entirely on it.

- I’m also shifting the final product slightly! Instead of just having a collection of artworks, I’m aiming to produce an artbook similar to that of Wizards of the Coast’s Dragons of D&D book (Herman Et. Al., 2024).

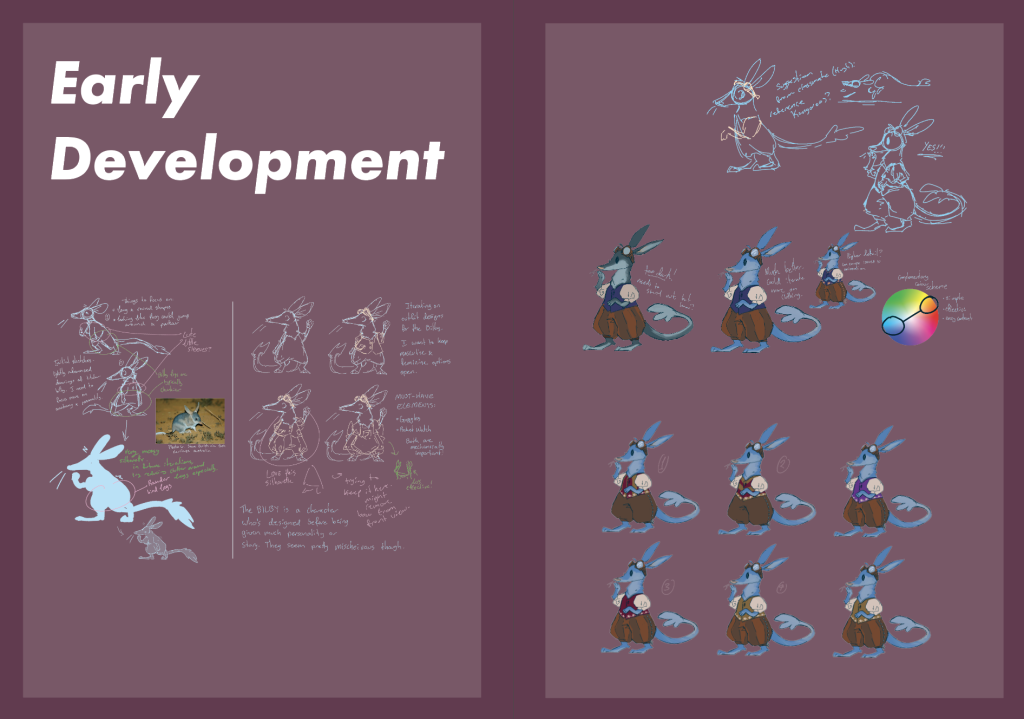

My new project will be focused on an idea for a video game I had back in 2023, currently called BILBY. Following the titular Bilby character through a 2D platformer, players will use physics (as in the science subject)-based puzzle mechanics to bend reality to their will and progress towards the end of the game.

The current story is that Bilby is trying to escape a black hole which is slowly eating the world they live in. They make progress with the help of a mysterious moth friend who knows more than most moths should about the mechanics of the universe and the goggles Bilby found that let them see the layers of said universe.

The concept for my DA has obviously expanded beyond the scope of just one semester, so I’ll be presenting an incomplete artefact at the end of semester. The main goal, however, is to make a smaller artbook on the character design process for the game! This is a far more reasonable goal to reach, particularly considering character design is an area I’m most experienced in when it comes to design and concept art.

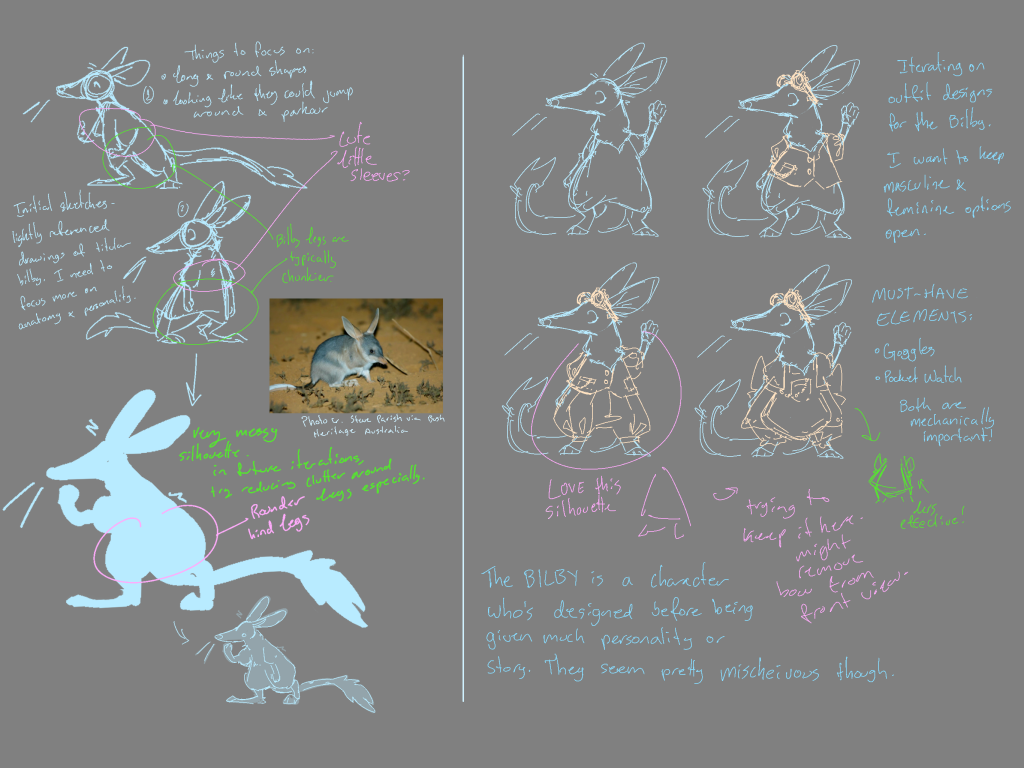

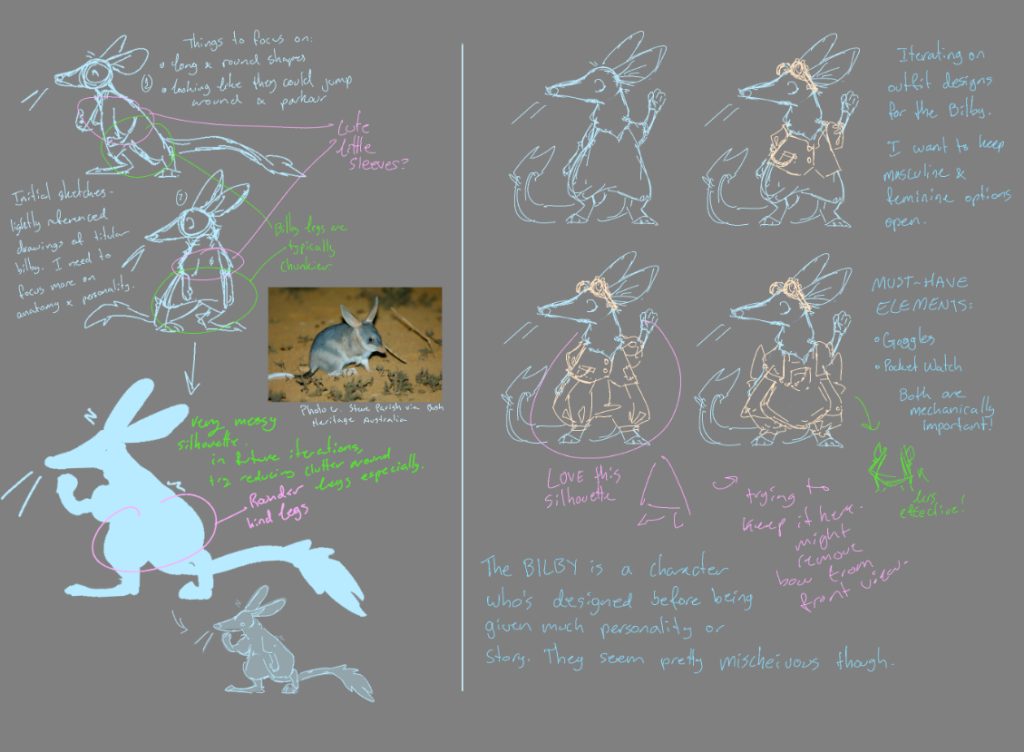

As for what I’ve done so far, due to edits made to the project I haven’t yet made it past the thumbnailing stage of my project, but I took two different approaches.

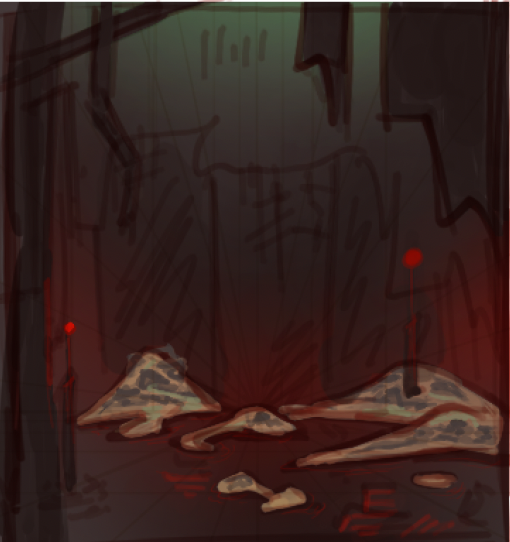

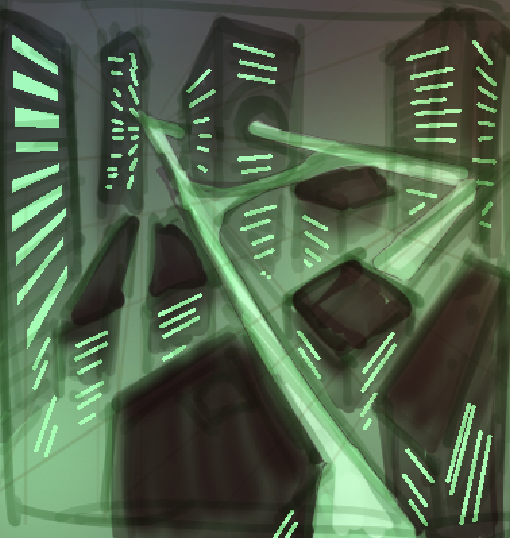

These were the extent of my work on the initial idea, halted early due to the sudden realisation I couldn’t do what I intended with my DA. These are of two separate districts within the world of the tabletop game, and my main goals were to use lighting and scale to really make the world feel foreboding and unforgiving. I had a description I was working off, as well as my own knowledge and ideas, so I started on colour immediately which isn’t usually the case in concept art. Despite that, I still consider these thumbnails due to how sketchy and loose they are- they each only took me around 30-45 minutes.

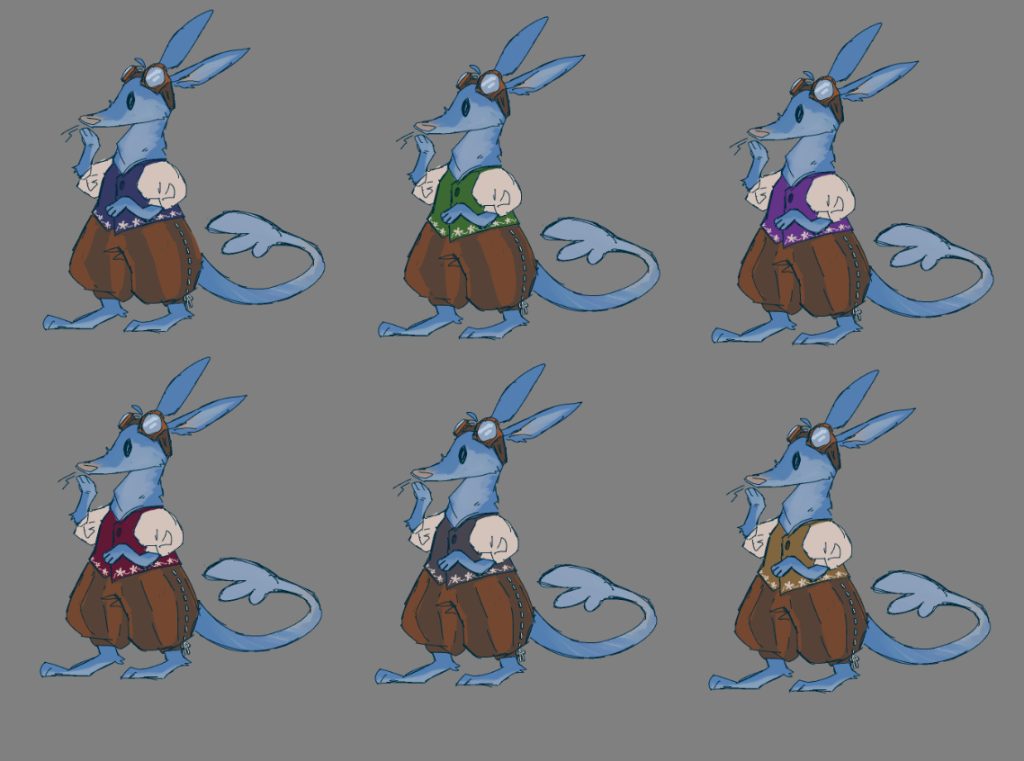

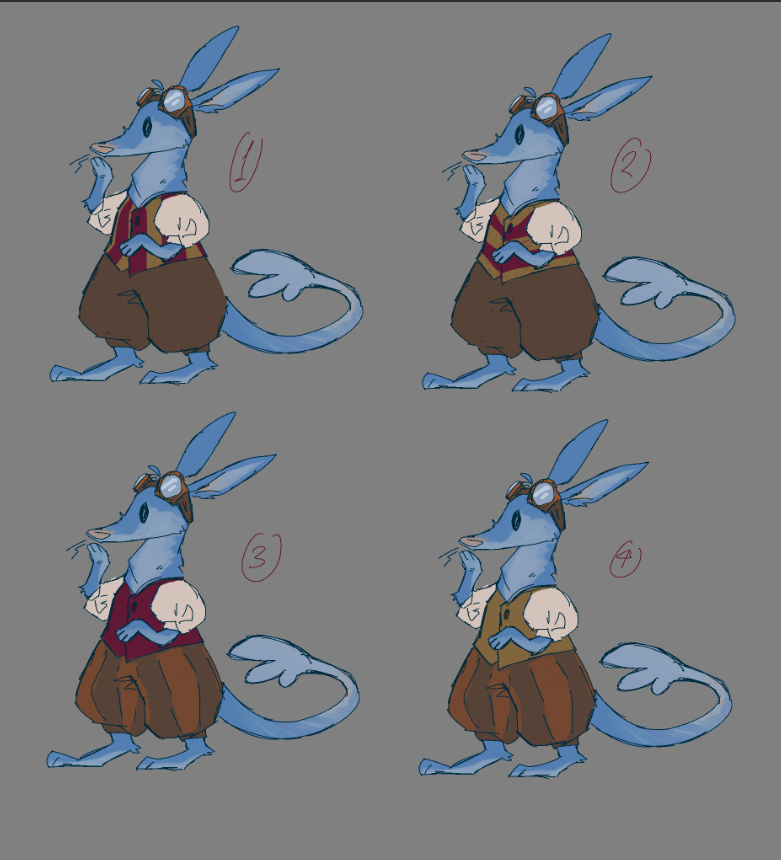

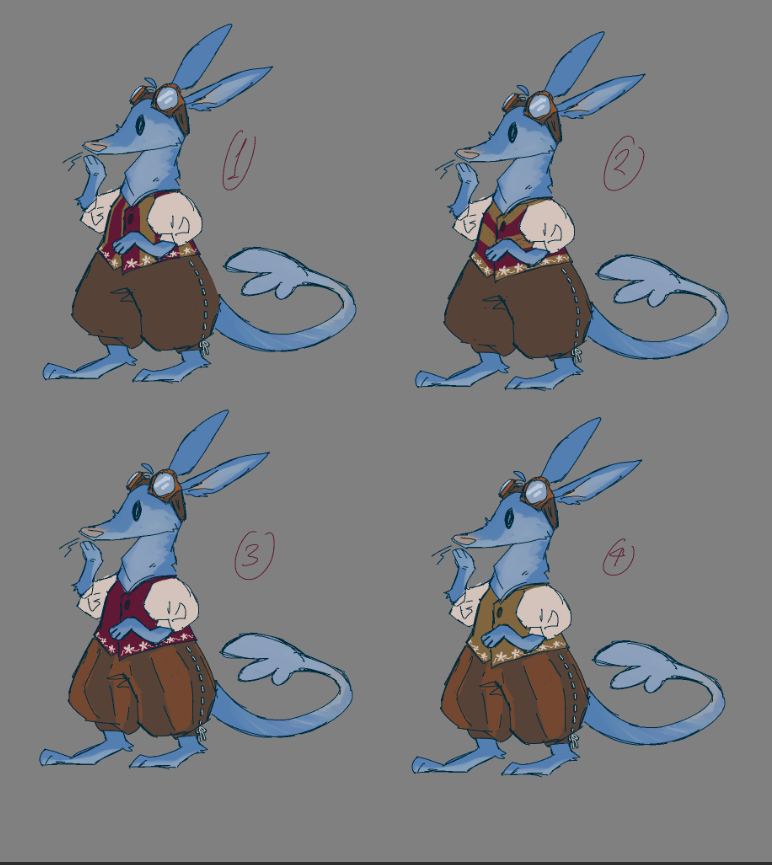

In comparison, the much more recent BILBY concept art took around an hour, and focused much more heavily on shape language and silhouette in the main character’s design. I’m still not fully happy with them, but this initial page of exploration is also only the first step towards a more complete design and concept, so I’m happy with where I am. Over the hour I spent on this page, I made several quick sketches of the character, taking notes and bringing those elements into the next iteration.

Overall the project is going smoothly, and I’m interested to see how it progresses over the next few weeks. The intent is to post updates here every other week, so I’ll see you then!

Bibliography

Anonymous & Unknown Worlds n.d., SN LostRiver Large, Fandom.com.

Beat Suter, Mela Kocher, René Bauer & Fabricatore, C 2018, Games and Rules Game Mechanics for the»Magic Circle«, Bielefeld Transcript Verlag, pp. 87–111.

Honkanen, T 2017, Creation of concept art for an action role- playing game

Höök, E 2023, ‘Gameplay Mechanics and Character Design Considering Climate’, Thesis, South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences.

Hunicke, R, Leblanc, M & Zubek, R 2004, (PDF) MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research, ResearchGate.

Leorke, D 2022, ‘Post-casual Play Affect, Demand and Labour in Digital Gaming’, Digital Culture and Society, vol. 7, no. 1.

Ostrowski, A & Vacala, P 2024, Dragons Of D&D, Wizards of the Coast, pp. 1–63.

Parish, S & Bush Heritage Australia n.d., Bilby, Bush Heritage Australia.

Wu, Y 2012, ‘ the Style of Video Games graphics: Analyzing the Functions of Visual Styles in Storytelling and Gameplay in Video Games’, Thesis, Simon Fraser University, pp. 87–96.

Week 13: Contextual Report and my DA

This semester, my Digital Artefact and research have been focused on Concept art, and its role in the game development process.

In doing this, I’ve made an in-progress artbook with my concept art for an ongoing video game concept I’m working on, currently titled BILBY. It’s a puzzle-platformer based around HSC physics concepts, and uses changes in the environment around the player character to represent different “layers” of reality. Because they’re so static, I ended up focusing on the character design for the Bilby in this DA, and thus have a ton of development art of them in my work.

Using Subnautica’s biome concept art as a case study, I set out this semester to learn how Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics impacted the concept art process, and encountered some interesting ways to include the feedback loops present in the framework not only in my art and design itself, but also in my process. I quickly learned that outside of a team context, working on concept art one part at a time was time-consuming and challenging, as game elements are made to work within the context of each other. A character design can exist in a vacuum, but without an environment or mechanical elements the MDA framework doesn’t function.

Part 1: Character Design

Above: The art posted as part of my update blog post between weeks 7 and 13. All of these were taken from my working document.

One of two major challenges within my DA project was figuring out how to make my work public-facing, and how to post updates within the rules of the task. As a result I ended up only having one blog post by the end, but I’d managed to demonstrate significant progress during the time I’d spent trying to work out what to do.

Basing my iterative process on that of Alieva in their bachelor’s thesis The Language of Colour in Character Design (2023), I tried to make the Bilby look inquisitive and friendly to match their body language and actions. I used many round, triangular shapes within the design, but also brightened their fur to an unnaturally bright shade of blue. While also increasing contrast and looking fantastical, the colour carries symbolism of calmness and logic that impacts the design’s affect on the viewer’s interpretation of their personality. I initially had their vest as blue because of this, but the similarity in hue led to a less effective design, and i settled on a cool-toned red for its more energetic connotations, even with the dark shade.

Contrast was significant to me in the design of the Bilby not only for their environment, but also as it led to part of my research on colour, and Aloumi’s PhD Thesis The Effect of colour contrast combinations on the simplicity and complexity of design. (2013) . In this, Aloumi discusses Itten’s theory of colour contrast and the many methods of achieving it– I ended up using cold-warm contrast (colour “temperature” based in its relative position on the colour wheel) and Complementary contrast (The use of colours opposite on the colour wheel).

Top: Chart of colour symbolism. Unknown author, from Fifteendesign.co.uk n.d.

Bottom: Final Bilby iteration with shapes highlighted.

Contrast was significant to me in the design of the Bilby not only for their environment, but also as it led to part of my research on colour, and Aloumi’s PhD Thesis The Effect of colour contrast combinations on the simplicity and complexity of design. (2013) . In this, Aloumi discusses Itten’s theory of colour contrast and the many methods of achieving it– I ended up using cold-warm contrast (colour “temperature” based in its relative position on the colour wheel) and Complementary contrast (The use of colours opposite on the colour wheel).

Use of colour in design work is significant for the dynamic ways audiences interact with designs and their own associations with those colours and symbols. Looking back at the MDA Framework and its importance to game design due to its own interactivity, we can see how audiences interact with all aspects of a game, including its visual appearance.

In Subnautica’s concept art, we see a wide variety of colour palettes and colours in general- Bright, fresh blues and deep reds are contrasted with pinks and sandy yellows. In this context, it’s easier to interpret the whole image rather than its constituent parts, which is where I went wrong somewhat with my own concept art.

The above artworks treat the environment as a character itself, and thus use the colours within the art to portray the personality of that location. Both works here are depictions of “safe” areas, though they both establish very different tones with the colouration used- Cotton Anemone (Updated) being far more moody than Mushroom Forest has a feeling of serenity to it with its more muted colour palette, with the latter being bright, colourful, and full of life implying much more activity. They’re also both heavy in round shape language, connoting “Completeness, gracefulness, playfulness,… unity, protection…” (Fogelström 2013) . The design of these areas, despite the less-than-ideal context in-game, makes them feel more friendly and appealing to be in than if they had been given darker colouration or sharper shape language.

Functionally within their respective games (Cotton Anenome (Updated) is actually concept art for Subnautica’s sequel), both biomes are actually rarely needed to be visited by players, having few points of interest or unique materials. They are, however, great locations for the base building elements of the games due to their aesthetic qualities and closeness to other, more important places. Both biomes achieve this with their interesting use of shapes and colours, derived from these works of concept art.

Part 2: Art in Context

Following a significantly accelerated version of the game design process, the next bit of work I did was to test animation of the Bilby design.

Prompted by Höök’s writing on how technical limitations (in this case, animation) can impact a character’s design, I made a very basic animated run cycle of the Bilby, paying attention to their shape language so it stayed consistent throughout.

While I already had animation in mind when creating the Bilby, some elements proved much more difficult to animate than I thought, and thus were simplified in my final pass of the design. One element I elected to keep despite the difficulty, however, was the stitching detail along the sides of the pants (Not pictured in the final run cycle). This was mostly because it added some character to the pants, and I know that with colouring in place and more attention to detail in my linework I’d be able to keep it far more consistent than in the sketchy style of the rough animation I did.

It’s important to consider and use animation in the design process, particularly in character design as a major way character designs achieve affect is through how they move. Much like colour and shape language, body language and acting in animation is vital to how audiences perceive the design.

The point I reached by the end of this class isn’t a whole lot, but that’s okay!

Above is the layouts I do have for the book so far. It isn’t published anywhere yet of course (a 3 page book is. Lame) but I’ll post it to my blog in higher quality for the purpose of this task.

Overall, this semester has been a nightmare of stumbles in the actual progress of making the research and artefact parts of this project, but the product at the end is one I’m proud of, and honestly it isn’t all that bad of a start despite the more focused nature not being what should be done in the concept art process. Moving forward with my research in consideration, I’ll need to look more deeply into environment design and get into the weeds of the mechanical and dynamic elements of the game.

Bibliography

Alieva, S 2023, Sarra Alieva THE LANGUAGE OF COLOUR IN CHARACTER DESIGN.

Aloumi, A 2013, e E ect of Colour Contrast Combinations on the Simplicity and Complexity of Design.

Anonymous & Unknown Worlds n.d., SN LostRiver Large, Fandom.com.

Beat Suter, Mela Kocher, René Bauer & Fabricatore, C 2018, Games and Rules Game Mechanics for the»Magic Circle«, Bielefeld Transcript Verlag, pp. 87–111.

Honkanen, T 2017, Creation of concept art for an action role- playing game, viewed 7 May 2023, <https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/125471/Honkanen_Timi.pdf>.

Höök, E 2023, ‘Gameplay Mechanics and Character Design Considering Climate’, Thesis, South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences.

Hunicke, R, Leblanc, M & Zubek, R 2004, (PDF) MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research, ResearchGate.

Leorke, D 2022, ‘Post-casual Play Affect, Demand and Labour in Digital Gaming’, Digital Culture and Society, vol. 7, no. 1.

Lindsay, K 2018, How Colour Influences Our Decision: Colour Psychology in Design, Fifteen.

McCormack, JP, Cagan, J & Vogel, CM 2004, ‘Speaking the Buick language: capturing, understanding, and exploring brand identity with shape grammars’, Design Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1–29.

Nat Geo WILD 2021, Meet The Bilby of Taronga Zoo | Secrets of the Zoo: Down Under, YouTube.

Ostrowski, A & Vacala, P 2024, Dragons Of D&D, Wizards of the Coast, pp. 1–63.

Parish, S & Bush Heritage Australia n.d., Bilby, Bush Heritage Australia.

Wu, Y 2012, ‘ the Style of Video Games graphics: Analyzing the Functions of Visual Styles in Storytelling and Gameplay in Video Games’, Thesis, Simon Fraser University, pp. 87–96.